Thank you for attending my virtual poster session for JEN 2022! This site presents my research on the flamenco compás as approached by jazz musicians. Musical examples are hyperlinked to YouTube pages where available and set to begin with the excerpt in question. You can also hear most of these songs on this Spotify playlist. Please visit my live Zoom chat where I will be answering questions and explaining my research in greater detail, and email me at bthestark@gmail.com with any further questions or feedback.

The topic of this presentation is the manner in which jazz musicians have interacted with the flamenco 12-beat metric compás in jazz settings of the flamenco styles bulerías, alegrías, and soleares. Examples will be provided from both American and Spanish jazz performers, with a discussion how their performance does or does not reinforce the distinctive accents of the flamenco compás.

COMPÁS

Compás is the general term for a rhythmic cycle in flamenco. Bulerías, alegrías, and soleares are three styles (or palos) which employ a distinctive twelve-beat compás with accents on beats 3, 6, 8, 10, and 12. Counted from “beat one,” the twelve beat compás looks like this (accented beats are bold):

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

However, the pattern can often be heard starting on beat 12, especially in faster styles such as alegrías and bulerías:

12 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

Flamenco metronomes are often represented as a clock face, and often contain standard handclaps (palmas) and cajón patterns to facilitate stylistic practicing.

Music that employs compás is often notated in the 5-measure pattern 3/4 + 3/4 + 2/4 + 2/4 + 2/4, emphasizing the alternation between three-beat and two-beat groupings by placing accented beats 12, 3, 6, 8, and 10 on downbeats. This works especially well in lighthearted styles like the guajira (EXAMPLE 1) in which chords change on the first three- and two-beat groupings.

However, most often when you hear a twelve-beat compás, the accents are defamiliarized by a primary emphasis on beat 3 (in which harmonic dissonance is often introduced) and beat 10 (in which the dissonance is resolved). This corresponds to the FINAL measures of 3/4 and 2/4 in examples notated this way. EXAMPLE 2 reproduces a common harmonic pattern from bulerías. In this example, the A7(b9) is understood as the Phrygian tonic, with Bb7 and Gm7 serving a dominant function - the recording in the hyperlink uses slightly different chord changes with the same effect.

I use a variety of meters in the musical examples employed throughout this study. I chose each meter with the following considerations in mind: 1) my interpretation of the performer or arranger’s MUSICAL INTENTION; and 2) my own ANALYTICAL PURPOSE for each example. In each example, compás counts are indicated ABOVE the staff, with accented compás beats in larger type-setting and bold to emphasize points where the performances align with or deviate from compás accents.

BULERÍAS

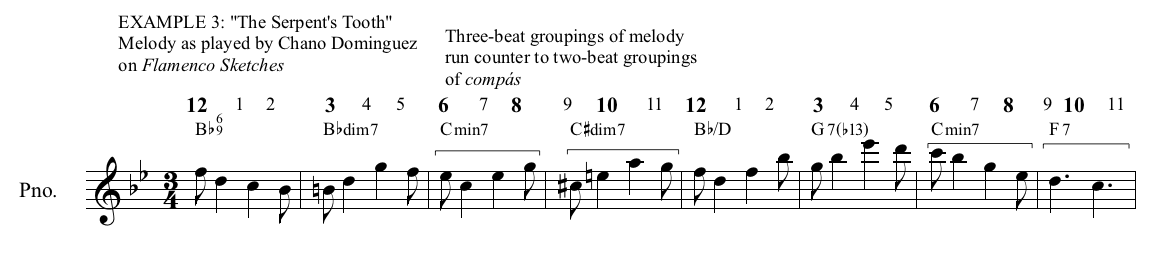

Jazz musicians are often drawn to the flamenco bulerías style because its rapid tempo makes it a suitable vehicle for virtuosic improvisation. Flamenco performers consider bulerías to be a cante chico style, that is, a festive and playful style of flamenco performance which is therefore well-suited to compositions outside of the standard flamenco repertoire. Spanish jazz musicians frequently adapt existing jazz standards into the 12-beat compás of bulerías. In some instances, the precise accent patterns of the compás are often glossed over, as in the A sections of Chano Dominguez’s performance of Miles Davis’s composition “The Serpent’s Tooth” from his 2012 album Flamenco Sketches (EXAMPLE 3). Here, Dominguez divides the 12-beat pattern into four even groups of three, resulting in an uptempo jazz-waltz effect.

The ensemble’s understanding of this piece as a bulerías is revealed in the first B section of this performance (EXAMPLE 4), in which bassist Jorge Rossy begins alternating between three-beat and two-beat patterns aligning with the accents of the 12-beat compás.

A fun and playful bulerías adaptation is Spanish saxophonist Jorge Pardo’s performance of “Donna Lee” on his 1991 release, Los Cigarras Son Quizá Sordas. Pardo executes large chunks of the melody as originally composed in quadruple meter, underscored by a driving bulerías beat. The matching of the melody to the compás pattern often seems entirely arbitrary, creating something of a long-running hemiola. However, Pardo takes care to begin his phrases in such a way they end on beat 10, preserving the typical compás resolution and providing a satisfactory conclusion for listeners attuned to the rhythms of bulerías. This is especially evident in the second half of the melody, reproduced in EXAMPLE 5.

Chick Corea has been recognized as one of the first American jazz musician to develop a deep understanding of flamenco music, and his album Touchstone (featuring flamenco guitarist Paco de Lucía) has been said to contain the first true flamenco-jazz recordings. One of these songs is “The Yellow Nimbus,” which is not only set to a bulerías rhythm but contains melodic lines that resemble traditional flamenco falsetas (guitar fills that traditionally occur between vocal verses). EXAMPLE 6a reproduces a typical bulería falseta (solo guitar interlude) taught to me by flamenco guitarist David Chiriboga (the transcription skips repetitions heard in the recording and is transposed to match EXAMPLE 6b). EXAMPLE 6b is a transcription of a falseta-like excerpt from “The Yellow Nimbus.” Note how Corea’s line follows a similar harmonic shape with the addition of over-the-barline phrasing that provides a contemporary jazz sensibility.

(This discussion of Touchstone and “The Yellow Nimbus” would not be here were it not for Sergio Pamies Rodriguez’s fabulous 2016 dissertation, cited at the bottom of this page).

ALEGRÍAS

Alegrías is a cante chico style that tonicizes to a major key, as opposed the Phrygian tonic employed by most flamenco styles. Many traditional alegrías vocal melodies translate naturally to instrumental interpretation, and contemporary flamenco guitarists often accompany them with chord progressions reminiscent of American Songbook standards. However, alegrías is not adapted to jazz contexts as frequently as bulerías, perhaps because its slower tempo requires that the performer pay more careful attention to the challenging harmonic asymmetries of the twelve-beat compás. I will present two jazz adaptations of alegías in the hopes of demonstrating the suitability of this style to jazz performers.

In “Tirititran,” released on Bob Belden’s 2011 production Miles Español, Spanish bassist Carles Benevant adapts a traditional alegrías melody to an AABA form with a rhythm-changes bridge with no precomposed theme. Chick Corea’s initial performance of the A section melody is reproduced in EXAMPLE 7, with Benevant’s bassline underneath to demonstrate the alignment of the harmonic rhythm with the accents of 12-beat compás (the example begins at 1:38, not 1:56 as stated below).

Corea recorded this piece again on Orvieto, a 2011 duo album with Italian pianist Stefano Bollani. In this performance, perhaps due to Bollani’s unfamiliarity with flamenco rhythms, Corea elects to treat the harmonic rhythm as a steady series of three-beat groupings (EXAMPLE 8), similar to Dominguez’s approach in “The Serpent’s Tooth.” This stands as an example of how a performance of alegrías can be simplified for jazz performers who have not yet seriously studied flamenco rhythms.

EXAMPLE 9 reproduces the chorus and solo section of my own arrangement, “Path By Cigarslight,” in which I elected to isolate a longer section of the alegrías melody as the primary vehicle for improvisation. This contains resolutions to secondary key areas including #vii dim7/ii and V7/IV which allows jazz improvisers to deploy their typical harmonic vocabulary, with the added challenge of lining up resolutions with the asymmetrical harmonic rhythms of the twelve-beat compás.

SOLEÁ/SOLEARES

Of the styles explored in this presentation, soleá/soleares (the two terms are used interchangeably) is the only one considered cante hondo, or “deep song.” This style typically deals with heavy emotions, and the lyrics commonly deal with themes of solitude, suffering, and death.

Studying soleá/soleares provides a chance to answer the question that has been simmering throughout this study: What about “beat one”? Why would flamenco musicians give primary importance to a non-accented beat when other accented beats (especially beat twelve) make so much sense as the first beat?

The answer is that, in flamenco styles generally, the musical phrase is understood to begin on beat one. In the faster and lighter styles such as bulerías and alegrías, this is often less apparent, and certainly does not often apply when adapting pieces like “Donna Lee” or “The Serpent’s Tooth.” However at the soleá’s slower tempo, the function of beat one is much more apparent. Often beat twelve (which we have treated as the first beat in examples up to this point) is not emphasized at all!

This may explain why Gil Evans, in his composition “Solea,” is the only example I will present in which beat one of a measure lines up with beat one of compás. Although Evans had never been to Spain nor studied formally with flamenco musicians, his intuitive understanding of compás is clear in the march-like snare ostinato that occurs throughout the performance, reinforced by a brass ostinato doubled at the octave in the woodwinds. This ostinato is presented in EXAMPLE 10b. EXAMPLE 10a shows a typical soleares guitar pattern by flamenco guitarist Melchor de Marchena that may have inspired Evans’s ostinato - note how the lower line of the guitar part in the first three beats matches the top line of the first three beats of the brass ostinato.

Perhaps due to the serious, cante hondo nature of the soleá, most jazz interpreters of this style have elected to perform straightforward instrumental renditions of traditional vocal melodies accompanied by flamenco guitarists. Such recordings have been made by saxophonist Pedro Iturralde (“Soleares,” accompanied by Paco de Lucía for his 1967 Jazz Flamenco recording); flutist Jorge Pardo (“Duende,” accompanied by Niño Josele on Miles Español); and guitarist Gerardo Nuñez (“Un Amor Real,” with upright bassist Renaud Garcia-Fons playing the melody on the 2000 release Jazzpaña II). I participated in this tradition myself, releasing “With You Through the Inferno” on YouTube in May 2021 in collaboration with guitarist David Chiriboga. EXAMPLE 11 is an excerpt of the vocal soleá that I transcribed to perform on saxophone.

My final example is a variation on the soleá pattern I wrote in my composition “Alegrías por Soleá,” recorded by UNT’s One O’Clock Lab Band on their release Lab 2016 (EXAMPLE 12). I present this ostinato to offer a stepping stone for others interested in composing or performing jazz pieces that draw from the flamenco style.

FOR FURTHER READING:

Pamies-Rodriguez, Sergio. “The Controversial Identity of Flamenco-Jazz: A New Historical and Analytical Approach.” DMA diss., University of North Texas, 2016.

- Contains an excellent overview of the evolution of flamenco-jazz, beginning before Miles Davis’s Sketches of Spain and culminating with Chick Corea’s Touchstone.

Manuel, Peter. “Flamenco Jazz: An Analytical Study.” Journal of Jazz Studies 11 No. 2 (2016): 29-77.

- An compendium of characteristics of the flamenco-jazz genre as it has emerged in recent decades.

BRIAN STARK’S FLAMENCO-JAZZ PROJECTS TO DATE:

“Alegrías por Soleá,” composition for big band recorded by the One O’Clock Lab Band on Lab 2016.

”La Apertura de Las Semillas,” composition for big band recognized by the Ithaca College Jazz Composition Contest in 2016.

”Path By Cigarslight,” composition for big band performed at Brian’s Master’s composition recital in 2017.

The Illinois Flamenco-Jazz Project (YouTube playlist), a collaboration with guitarist David Chiriboga performed at the Spurlock Museum in October 2019.

La Juerga de Primavera (YouTube playlist), a collection of remote and in-person recordings featuring Chiriboga, premiered in May 2021.

The Urbana Flamenco-Jazz Reunion, in-person reunion concert with Chiriboga, sponsored in part by the Urbana Arts Grant, in August 2021.

BRIAN STARK BIO

Brian Stark is Professor of Music at the University of Illinois at Springfield, where he directs the Jazz Band and teaches applied saxophone. He is completing his Doctorate of Musical Arts in Jazz Performance at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and is currently ABD. His dissertation, “Finding Flamenco in Sketches of Spain,” identifies likely sources for the flamenco-inspired music of Miles Davis and Gil Evans. Brian’s flamenco-jazz projects have been funded by the Center for Advanced Study, the Center for Global Studies, Urbana Arts and Culture, the Urbana Free Library, the European Union Center, and the Spurlock Museum of World Cultures. He is also a leader of the Fiddle-Sax Fusion Band and Gobbo-Stark Quartet, both of which will have recorded albums for release in 2022.